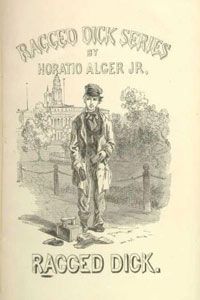

If you ever come across a trove of battered old hardcover novels published in the United States in the 19th century, take a minute to thumb through them. Chances are high that the beginning and end of each book will yield a common theme. The novel's story will probably begin in squalid living conditions -- a tenement in Brooklyn, perhaps. However, the book will usually end in an entirely different setting. By the novel's conclusion, the cluttered and menacing mental and physical environment of the slum will have been replaced with marbled floors, domestic servants, cigars and brandy.

Within the yellowed pages of these books, you'll find an invariable narrative: The protagonist rose from squalor to wealth through hard work and determination. Of course, he or she accomplished this within the framework for success provided by the capitalist system, which was beginning to make the still young U.S. a very wealthy country.

Advertisement

At the core of capitalism is the so-called entrepreneurial spirit: Anyone who's willing and able to cultivate an idea into a business has a chance to succeed. Under capitalism and the free market, everyone's offered the same opportunity for success. That said, this shot at the big time is a largely theoretical one. Some entrepreneurs simply don't meet the criteria that lending institutions rely on to avoid risk. Most bankers are, after all, capitalists as well, and the best way for a lender to ensure a profit is to lend to those likeliest to repay the loan. It's a caveat (some would say, flaw) to the capitalist system: the door to wealth or self-sufficiency is open only to those who meet certain standards. Unfortunately, the poor generally don't meet those standards.

Another type of lending has emerged to combat this vicious cycle, known as microlending. Compared to traditional lending practices found in capitalist economies, microlenders are mindlessly risky in the loans they make: They loan money to the indigent, those without collateral, career changers and those without any work experience. To some, the concept of microlending is merely a noble idea that doesn't work in practice or an innovation that will eventually lead to a developed, globalized world. Who's right?

Advertisement