Helping to clinch his eventual victory, Barack Obama declared in a 2008 presidential campaign ad, "The old trickle-down theory has failed us" [source: YouTube]. This statement and Obama's victory resound like a death knell to an economic mentality that some say served to line the pockets of the rich. However, the trickle-down theory to which he refers remains a highly controversial topic. That Obama seeks to end trickle-down policy is certain, but what the theory really suggests and whether it has succeeded have been less clear.

Advertisement

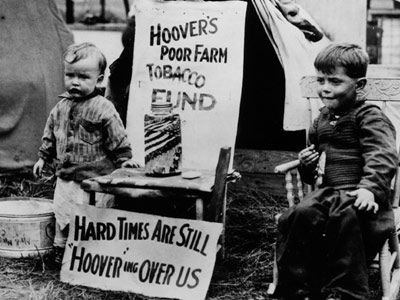

To understand trickle-down theory, we have to iterate some economic basics. First off, all capitalistic economies undergo natural ups and downs. In times of prosperity, economic activity is high, and jobs are easy to find. In times of recession, a country's economy produces less, and people have trouble finding jobs. Government steps in to try to help smooth out these fluctuations and dull the pain of sharp economic downturns.

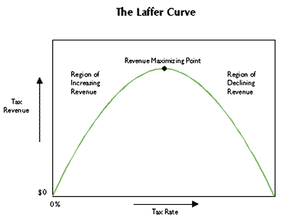

Adjusting the tax policy is one way to affect the economy, and the U.S. government has been using tax policy this way almost since the inception of the national income tax in 1913. Although economists agree that changing how a government taxes its citizens can have some dramatic effects on an economy, they disagree on which policy is best. Trickle-down theory represents one such idea that can supposedly spur economic growth.

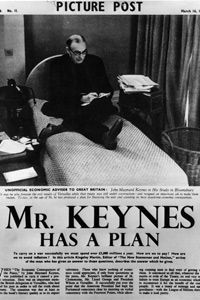

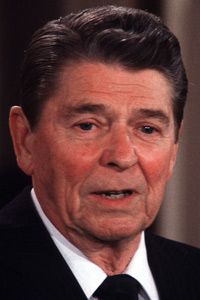

In a nutshell, trickle-down theory is based on the premise that within an economy, giving tax breaks to the top earners makes them more likely to earn more. Top earners invest that extra money in productive economic activities or spend more of their time at the high-paying trade they do best (whether that be creating inventions or performing heart surgeries). Either way, these activities will be productive, reinvigorate economic growth and, in the end, generate more tax revenue from these earners and the people they've helped. According to the theory, this boost in growth will ultimately help those in lower income brackets as well. Although trickle-down economics is often associated with the policies of Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, the theory dates back to the 1920s. The name also has roots in the '20s, when humorist Will Rogers coined the term, saying, "The money was all appropriated for the top in the hopes it would trickle down to the needy" [source: Shafritz].

Rogers' comment cemented negative associations with the theory for several generations to come. Proponents of the logic behind the theory object to calling it "trickle-down" and argue that the name is inherently misleading. In the next few pages, we'll find out how trickle-down economics is supposed to work and why people argue about whether it does.

Advertisement