Debtor's prisons were abolished in the United States in 1833. Until that time, failure to pay what you owed could and did land you in jail. And debtor's prisons added a nice touch -- not only were you forced to pay your debt, but you were also forced to pay your prison fees. The question was, how? These prisons didn't allow work release, and prisoners didn't print license plates, so once in the lock-up, debtors were almost solely dependent on family or friends (or hidden funds that took imprisonment to shake from their pockets) in order to pay the bill -- sometimes less than a dollar.

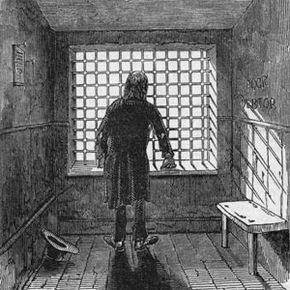

And while waiting for payment to drop from the sky, debtors could look forward to accommodations that toed the line between a jail and a dungeon. In 1736, a Maryland committee described the local debtors' prison as, "A place of restraint and confinement [that] has also been a place of death and torments to many unfortunate people" [source: getoutofdebt.org]. Not least among the torments was typhoid fever, which did wonders for the overcrowding of 18th- and 19th-century jails.

Advertisement

One of these unfortunate, incarcerated debtors was Robert Morris, who loaned the fledgling U.S. government $10,000 during the Revolutionary War. After land speculation went south, he defaulted on loans and landed in Philadelphia's Prune Street Prison.

Obviously, this tough-on-debt approach was supposed to deter people from taking on debts they couldn't repay. Unfortunately, it didn't work. In a 1758 letter titled "To The Idler," the English author and essayist Samuel Johnson wrote:

In other words, Johnson gave up on punishing users and recommended refocusing on suppliers. This kind of thinking eventually led to a national bankruptcy law in 1802 (springing Robert Morris from Prune Street), and the establishment of the Federal Trade Commission in 1914, which was -- among other things -- supposed to protect consumers from predatory lending practices that would result in impossible debts [source: FTC].

The irony in that last sentence makes a nice transition into the question of whether debtors' prisons really still exist.

Advertisement