The year was 1940. London, England was under siege. Night after night, German Luftwaffe bombers strafed the skies, raining fire and destruction upon the city. Thousands of people were killed, and more than a million were made homeless [source: Museum of London].

Across the Atlantic, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was deeply concerned. Though the United States military was strong, he felt that even more manpower and supplies would be needed to protect American cities if they were to come under attack. The country needed a civilian defense force.

Advertisement

During World War I, the government had established a Council of National Defense to coordinate resources for national defense and stimulate public morale. State and local communities set up their own defense councils to help direct efforts in health, welfare, morale and other activities, but these volunteer groups did not get involved in actual civilian defense because there wasn't a need. Military from other countries couldn't reach America because the aviation industry was still in its infancy.

By World War II, that had changed. Airplanes had become advanced enough for enemies to reach the United States. After launching a mission to London to observe the Blitz, New York City mayor Fiorello LaGuardia wrote an urgent letter to President Roosevelt stating, "The new technique of war has created the necessity for developing new techniques of civil defense" [source: FEMA].

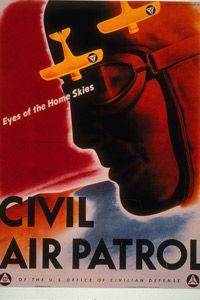

The president took this advice to heart, and on May 20, 1941, he signed an executive order establishing the Office of Civilian Defense (OCD). Roosevelt chose LaGuardia to oversee the new department.

The OCD was created to protect the general population in the event of an attack, keep up public morale if the United States were to enter the war in Europe and involve civilian volunteers in the country's defense. The OCD's jobs included establishing air-raid procedures, supervising blackouts and protecting against fire damage in the event of an attack.

LaGuardia's main goal was to protect the public. But first lady Eleanor Roosevelt thought the OCD's role should be expanded to also include public health and welfare, as well as to increase civilian participation (especially of female volunteers). LaGuardia didn't want to get involved with what he called "sissy stuff," so he eventually hired the first lady to head up these efforts as his assistant director [source: FEMA]. Eleanor Roosevelt founded the Civilian Participation Branch of the OCD.

Advertisement