Have you ever stood behind someone in line at the store and watched them shuffle through a stack of credit cards? Consumers with this many cards are in the minority, but experts say that the majority of U.S. citizens have at least one credit card, and the average number is about four, according to Experian.

It's true that credit cards have become important sources of identification. If you want to rent a car, for example, you really need a major credit card. And used wisely, a credit card can provide convenience and allow you to make purchases with nearly a month to pay for them before finance charges kick in.

Advertisement

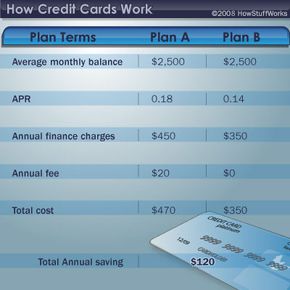

That sounds good in theory. But in reality, many consumers are unable to take advantage of these benefits because they carry a balance on their credit card from month to month, paying finance charges that average nearly 18 percent, but can go up to a whopping 30 percent or more. Many find it hard to resist using the old "plastic" for impulse purchases or things they really can't afford. The numbers are striking: At the end of 2020, American consumers carried $825 billion in collective credit card debt.

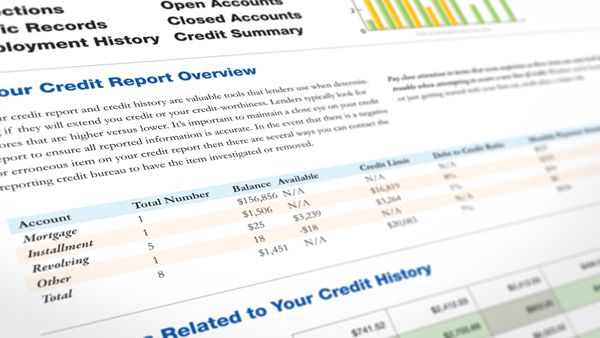

In this article we'll look at the credit card — how it works both financially and technically — and we'll offer tips on how to shop for a credit card. Experts say this should be a project on the scale of shopping for a car loan or mortgage. We'll also describe the different credit card plans available, talk about your credit history and how that might affect your card options, and discuss how to avoid credit card fraud, both online and in the real world.

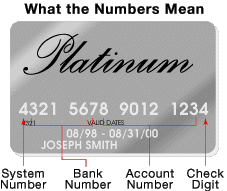

Let's start at the beginning. A credit card is a thin, plastic card, usually 3.37 by 2.13 inches (85.6 by 54 millimeters) in size. The dimensions are set by the International Organization for Standardization. The card contains identification information such as a signature or picture, and authorizes the person named on it to charge purchases or services to their account — charges for which they will be billed periodically. Today, the information on the card is read by automated teller machines (ATMs), store readers and bank and internet computers.

According to Encyclopedia Britannica, the use of credit cards originated in the United States during the 1920s, when individual companies, such as hotel chains and oil companies, began issuing them to customers for purchases made at those businesses. This use increased significantly after World War II.

The first universal credit card — one that could be used at a variety of stores and businesses — was introduced by Diners Club, Inc., in 1950. With this system, the credit card company charged cardholders an annual fee and billed them on a monthly or yearly basis. Another major universal card was established in 1958 by the American Express company.

Later came the bank credit card system. Under this plan, the bank credits a merchant's account as sales slips are received (this means merchants are paid quickly — something they love!) and assembles charges to be billed to the cardholder at the end of the billing period. The cardholder, in turn, pays the bank either the entire balance or smaller monthly installments, with interest (sometimes called carrying charges).

The first national bank plan was BankAmericard, which was started on a statewide basis in 1959 by the Bank of America in California. This system was licensed in other states starting in 1966, and was renamed Visa in 1976.

Other major bank cards followed, including Mastercard, formerly Master Charge. In order to offer expanded services, such as meals and lodging, many smaller banks that earlier offered credit cards on a local or regional basis formed relationships with large national or international banks.

Advertisement