If you're arrested in most cities and towns in America, you'll be fingerprinted, booked and tossed in a jail cell until the judge sets your bail. Technically, bail means any kind of conditional release from custody between your arrest and your actual trial date. But in most cases, bail means money.

Cash bail is one of the oldest ways of ensuring that an accused criminal shows up for trial. Dating back to the medieval Anglo-Saxons, cash bail allows a defendant to be released from jail before trial by giving the court cash or collateral. The money or property is returned to the defendant if, and only if, they show up to court.

Advertisement

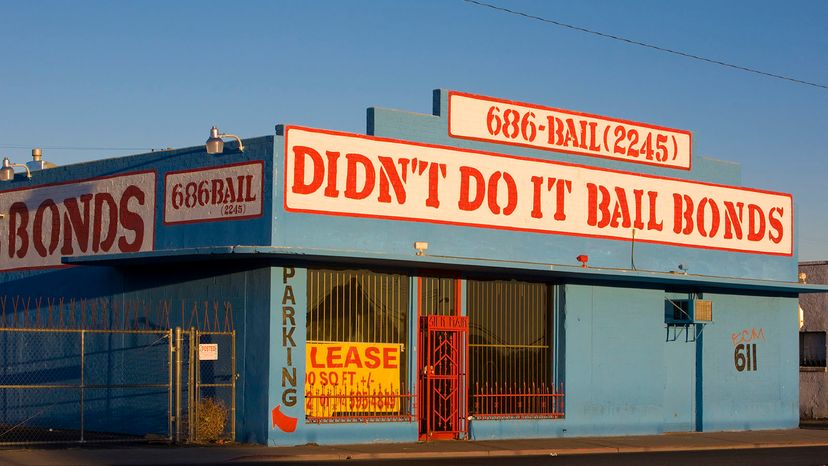

Today, most cash bails aren't paid directly by the defendant, but by a third-party bail bonds agent, also known as a surety bondsman. That's because the cash bail schedules used by most judges — X crime equals X dollars in bail — don't factor in a person's ability to pay. For example, if you were to look at the 2018 bail schedule for Orange County, California, you'd see that the bail for residential burglary is set at $50,000.

A bail bonds agent charges 10 percent of the full amount (nonrefundable) for your release and promises the court to pay the balance if you don't show up. They also promise to hunt you down and collect on your debt.

But bail bonds agents don't have to post bail for everybody. Some people, like drug addicts and repeat offenders, may be too risky. And others are simply too poor to cover the 10 percent fee. So they sit in jail awaiting trial, sometimes only for a few days, but often for months, and in extreme cases, for years.

Currently 443,000 people who haven't been convicted are sitting in America's jails awaiting trial, says the Prison Policy Initiative. That's seven out of every 10 people in jail who have yet to be convicted or sentenced. (Note that jails aren't the same as prisons. Jails are designed for shorter stays, whether it's a short sentence or pretrial detention.) The total number of Americans incarcerated in both jails and prisons is more than 2.3 million, according to a 2017 report by the nonprofit group.

The real crime, for criminal justice reform groups like the Pretrial Justice Institute, is that the cash bail system produces two very different outcomes depending on how much money the defendant can scrape together. A person arrested for felony assault, who poses a potential safety risk to the community, could walk free if they make bail. While a person arrested for misdemeanor shoplifting, could sit in jail for weeks because they can't come up with a few hundred bucks for bail.

"Money has now become the primary determining factor of whether or not you're released," says Rachel Sottile Logvin, vice president of the Pretrial Justice Institute, which advocates for eliminating cash bail entirely and "maximizing release" by moving to a risk-based system that assesses a defendant's threat to public safety if released, and his or her likelihood of appearing in court.

Bail reform isn't a new issue. Speaking at the 1964 National Conference on Bail and Criminal Justice, Attorney General Robert Kennedy concluded:

But despite being on reformers' radar for more than 50 years, only recently have city and state governments, and judges begun to really do something about bail. New Jersey passed bail reform in 2014 and launched its new assessment-based system in January 2017. The Maryland supreme court ruled in February 2017 that defendants can't be held in jail pretrial simply because they can't afford bail. And bills have been introduced in states like California, Connecticut and New York to reduce the reliance on cash bail for pretrial release.

"We've been around for 40 years as a nonprofit, and only in the last five has our phone been ringing off the hook," says Sottile Logvin, "but we've been waiting."

The bail bond industry has been lobbying hard against changes to the cash bail system, which it insists is still the best way to ensure that defendants won't skip out on their court date.

Jeff Clayton is executive director of the American Bail Coalition. He takes issue with the statistic that seven in 10 people in jail are awaiting trial and haven't been convicted or sentenced. Clayton insists that most detainees aren't there because they can't pay bail, but because the judge has placed them on "other holds" for violating probation or a pending charge in another jurisdiction. Also, to say they haven't been convicted ignores the fact that many have a long history of prior convictions.

"The real question," asks Clayton, "is what would the alternative [to cash bail] be and would it look any better?"

For that, there's really only one place to look, and that's the Pretrial Services Agency (PSA) in Washington, D.C. The PSA, an independent federal agency with a 45-year track record, is widely regarded as the gold standard of pretrial criminal justice reform. While cash bail is still legal in D.C. and used in rare cases, the PSA releases 80 percent of defendants on their own recognizance, meaning nothing but a pledge to return for trial.

Even without bail, PSA has seen 90 percent of released defendants appear at all of their scheduled court dates and 91 percent remain arrest-free between pretrial release and their trial date.

How does it work? The PSA uses a risk-assessment tool that calculates each defendant's real threat as a safety risk or flight risk, using metrics like the defendant's current charges, criminal history, age and other attributes (race not among them). Based on this assessment, the system recommends the "least restrictive, non-financial release conditions."

Next, an army of PSA caseworkers sits down with each defendant, particularly the higher risk individuals, to lower their barriers to success. There's on-site drug testing and an in-house drug treatment facility. Defendants with mental health issues are referred to community counseling partners. PSA can provide help with employment and housing to help disrupt cycles of poverty and crime.

If a defendant skips a court date, the judge doesn't automatically issue a bench warrant for his or her arrest. The PSA caseworkers conduct a "failure to appear investigation," which includes phone calls to the defendant, the defendant's family, to other jurisdictions and even to hospitals, if the defendant has known health issues.

All of this costs money. The PSA has 350 full-time employees (75 percent are caseworkers) with an annual budget of $65 million.

"Supervision and all these alternatives are hugely expensive," says Clayton of the American Bail Coalition, noting that New Jersey's new system, which follows the PSA model closely, may cost in the hundreds of millions of dollars to operate.

Leslie Cooper, director of the PSA, says that the agency's core tenants — risk assessment and release conditions tailored to that risk — are "scalable and replicable anywhere" and can be customized to fit a jurisdiction's budget. What's harder, says Cooper, is the culture shift that needs to happen from within.

"If a jurisdiction's culture of criminal justice has developed around the use of money bond as a system, particularly money bonds that are secured by third party bail bondsman, it's a huge cultural change to tell people that your system can be equally if not more effective when you take away money," says Cooper. "Nothing sells the case better than being able to say it works. And we have the numbers to prove it."

Advertisement