After Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans, millions of families were stranded or displaced, food and water was scarce, and public safety became an issue of grave concern. The city was in a genuine humanitarian crisis, and many were calling for aid from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

But following Hurricane Katrina, FEMA proved to be sluggish and unresponsive. The agency had trouble coordinating efforts between subordinate agencies, like the Red Cross and state departments, and delivering supplies to families that needed them.

Advertisement

President George W. Bush complimented the head of FEMA, his friend and appointee Michael D. Brown, but to the people in need of help in New Orleans as well as the press, Brown bungled the relief operation. In fact, the U.S. Congress held an investigation into the series of mishaps that made up FEMA's operations in New Orleans.

It was later revealed why Brown experienced hardship as the head of FEMA: Brown was the victim of a poor promotion. Put simply, he had risen to a job with responsibilities that he couldn't fulfill. Before his role as FEMA director, Brown served as the commissioner of judges for the International Arabian Horse Association. He excelled in that position, and as such, was promoted by President Bush into a role with greater responsibilities: that of FEMA director.

Brown was widely perceived to have failed in this position. To make matters worse, his incompetence was displayed as publicly as is possible, with the international media focusing their attention on his every misstep. Brown eventually requested to be removed from his position as FEMA director, with his famous question, "Can I quit now?" [source: CNN].

Brown was vilified by the media, but it's difficult not to commiserate with him. He was good at his previous job, and -- as is dictated by the American Dream -- when offered a position with more prestige, salary and potential for growth, he took it. The person who gave him the job had faith in his abilities, so why shouldn't he take the job? But Brown proves that a promotion isn't always a good thing.

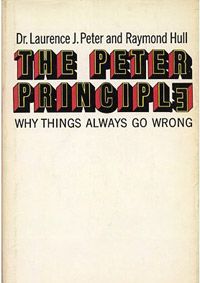

While the stakes aren't usually as high, promotions like Brown's happen frequently in business and government bureaucracies. A person who excels at his position is often rewarded with a higher position, eventually one that exceeds the employee's field of expertise. This is called the Peter Principle, an observation put forth in the late 1960s by Dr. Laurence J. Peter, a psychologist and professor of education [source: Business Open Learning Archive].

"In a hierarchically structured administration, people tend to be promoted up to their level of incompetence," or, as Dr. Peter went on to explain in simpler terms, "The cream rises until it sours." The Peter Principle has even found its way into Masters of Business Administration (MBA) curriculum.

So what does the principle imply about the structure of the companies that supply our livelihood and the governments that rule us? In this article, we'll learn about the Peter Principle and ways to combat it.

Advertisement