To a writer, self-publishing is an incredibly powerful and alluring concept. On the simplest level, it's an intriguing solution to an age old problem: How do you get your words to a wide audience (ideally, while earning some money along the way)? On a more artistic level, it is a unique extension of the creative process. Beyond putting words on the page, the self-publisher actually controls every aspect of authoring -- he or she creates the physical book and actively brings it to an audience. It's a uniquely harmonious and satisfying melding of art and business.

Advertisement

It's not easy, of course, but these days self-publishing isn't as difficult as you might think. Today, you can produce a substantial run of a quality book for as little as $5,000.

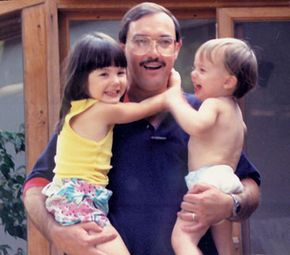

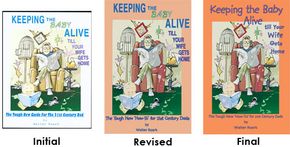

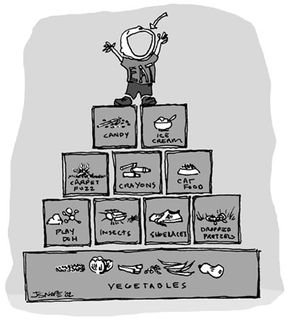

In this article, we'll walk through what you would do as a self-publisher, and we'll get some words of advice from an author who's actually been there. Walter Roark has published three books -- "Keeping the Baby Alive Till Your Wife Gets Home," "Keeping Your Grandkids Alive Till Their Ungrateful Parents Arrive," and "Keeping Your Toddler on Track Till Mommy Gets Back" -- and has had success with all of them.

Advertisement