Patents are the most complicated type of intellectual property, as well as the most restrictive. To patent an invention, you have to meet a number of requirements. First of all, the invention must be sufficiently novel. That is, it must be substantially unlike anything that is already patented, has already been on the market or has been written about in a publication. In fact, you can't even patent your own invention if it has been on the market or discussed in publications for more than a year.

The vast majority of inventions are actually improvements on existing technology, not wholly new items. The camcorder, for example, is essentially a combination of a video camera and a tape recorder, but it is a unique idea to combine them into one unit. It was so innovative, in fact, that when Jerome Lemelson first submitted the idea to the patent office in 1977, it was rejected as an absurd notion. When the invention was eventually patented, it launched a flood of portable video machines. If you search for the term "camcorder" in the U.S. Patent Office's database, you will find more than a thousand separate patents. A modern camcorder is a combination of hundreds of patented inventions.

Adaptations of earlier inventions can be patented as long as they are nonobvious, meaning that a person of standard skill in the area of study wouldn't automatically come up with the same idea upon examining the existing invention. For example, you can't patent the concept of making a toaster that can handle more pieces of bread at once, because that is only taking an existing invention and making it bigger. For an invention to be patented, it must be innovative to the point that it wouldn't be obvious to others.

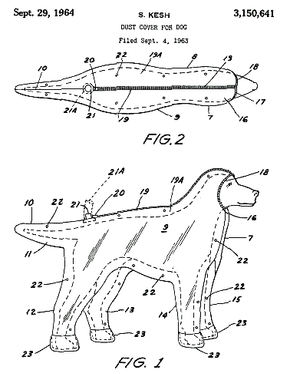

Another condition for patenting something is that the invention is "useful." Generally speaking, this means that the invention serves some purpose and that it actually works. You couldn't patent a random configuration of gears, for example, if it didn't do anything in particular. You also wouldn't be able to patent a time machine if you couldn't construct a working model. Unproven ideas generally fall into the realm of science fiction, and so are protected only by copyright law. The "useful" clause may also be interpreted as a prohibition against inventions that can only be used for illegal and/or immoral practices.

All a patent really does is give the patent-holder the right to stop others from producing, selling or using his or her invention. For the life of the patent (20 years in the United States), patent-holders can profit from their inventions by going into business for themselves or licensing the use of their invention to other companies. It is up to the patent-holder to actually enforce the patent; the government does not go after patent or copyright infringers. To enlist the government's help in stopping infringement, the patent-holder must take any infringers to court.

Some inventors, such as the late Jerome Lemelson, have spent a significant part of their careers battling infringers. Many large companies have been accused of appropriating inventors' ideas without compensating them for their work. Though Lemelson had patented crucial components in some of the most momentous technology of the 20th century, he spent much of his life struggling to get by. His critics charged that most of his ideas were based on projects companies were already pursuing. Eventually, Lemelson won out, amassing a substantial fortune late in life. He and his wife Dorothy used much of this money to assist other struggling inventors. In 1994, they established the Lemelson Foundation, a philanthropic organization dedicated to promoting and rewarding American inventors.

While patent law does protect most forms of invention, it does not apply to all great ideas. In the next section, we'll see what sort of things can be patented and which cannot.