For centuries, the currencies of the world were backed by gold. That is, a piece of paper currency issued by any world government represented a real amount of gold held in a vault by that government. In the 1930s, the U.S. set the value of the dollar at a single, unchanging level: 1 ounce of gold was worth $35. After World War II, other countries based the value of their currencies on the U.S. dollar. Since everyone knew how much gold a U.S. dollar was worth, then the value of any other currency against the dollar could be based on its value in gold. A currency worth twice as much gold as a U.S dollar was, therefore, also worth two U.S. dollars.

Unfortunately, the real world of economics outpaced this system. The U.S. dollar suffered from inflation (its value relative to the goods it could purchase decreased), while other currencies became more valuable and more stable. Eventually, the U.S. could no longer pretend that the dollar was worth as much as it had been, so the value was officially reduced so that 1 ounce of gold was now worth $70. The dollar's value was cut in half.

Finally, in 1971, the U.S. took away the gold standard altogether. This meant that the dollar no longer represented an actual amount of a precious substance -- market forces alone determined its value.

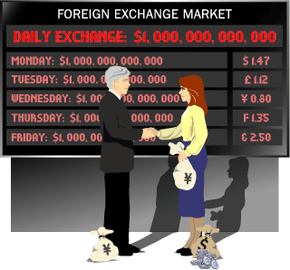

Today, the U.S. dollar still dominates many financial markets. In fact, exchange rates are often expressed in terms of U.S. dollars. Currently, the U.S. dollar and the euro account for approximately 50 percent of all currency exchange transactions in the world. Adding British pounds, Canadian dollars, Australian dollars, and Japanese yen to the list accounts for over 80 percent of currency exchanges altogether.