Political elections in the United States are expensive. And the cost of presidential elections in particular is high and climbing exponentially, which is why you so often hear about candidates' war chests during election years.

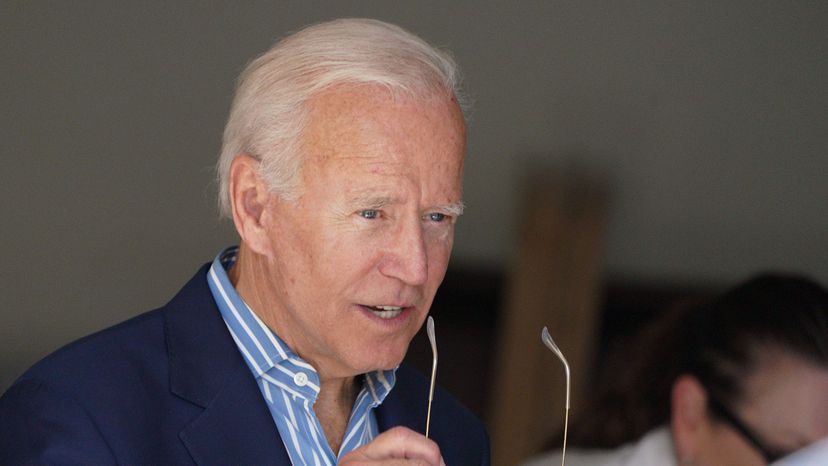

In the 2004 presidential election, George W. Bush and John Kerry raised nearly half a billion dollars in private funding in their bids to win the White House. Total receipts for all candidates surpassed $880 million for the primary and general election. By 2008, those numbers looked modest, as Barack Obama and John McCain raked in more than $1 billion for their contest, the first time a U.S. presidential election topped the billion-dollar mark. But the 2020 presidential election between Donald Trump and Joe Biden is expected to be the most expensive of all time, with the two having raised $3.2 billion by October 2020 [sources: Politico, Center for Responsive Politics].

Advertisement

The figures for all federal elections is even more mind-boggling. In 2016, a presidential election year, all 435 seats in the House of Representatives were also up for election, as were one-third of the seats in the Senate. The cost of all of those races? A whopping $6.5 billion [source: U.S. Department of State].

With this kind of money changing hands, it may leave you wondering where it goes and why it's necessary to raise that much. The fact is, getting the word out on a candidate's platform is becoming more and more expensive. Television and radio ads, billboards, mailers and signs are just a few of the places the money goes. The American public is inundated with messages from the political machine like never before.

Dealing with such huge sums of money also brings the potential for illegalities. Historically, elections around the world have been rife with scandal and corruption. In the United States, the Federal Elections Commission (FEC) has the task of keeping elections as clean as possible by regulating donations, spending and public funding. In addition to the FEC, grassroots organizations like the Center for Responsive Politics, Consumer Watchdog and Common Cause keep a close eye on how money is raised and spent. Congress and the Senate have debated campaign finance reform for decades, and the laws in place have been difficult to enforce because of loopholes and tricky bookkeeping.

In this article, we'll look at the history of campaign finance in the United States, how funds are raised and spent today, and what the government is doing about campaign finance reform.

Advertisement