Tipping makes zero sense. Is it a reward for good service? Studies show that tips don't go up or down significantly based on the quality of service. Does tipping attract and retain better wait staff? Not really. Is it a bribe so the waiter won't spit in your soup the next time you come? Probably depends on the waiter.

In most countries, a service charge is included in the bill. However, in America, instead of an up-front service charge, diners hand over 15 percent (or more) of the price of the meal to the server. It's not required, but it is customary. But this seemingly generous practice has some nasty hidden costs.

Advertisement

For starters, the existence of tipping allows restaurants to pay servers a federal minimum wage of $2.13 an hour. So, waiters in most states basically live and die by tips. The result is that tipped workers are twice as likely to live in poverty and depend on food stamps as other workers.

Then there's the opposite problem. In stronger restaurant markets like big cities, the existence of tipping means that waiters in busy restaurants end up making a lot more money than the cooks and dishwashers, who get paid a fixed hourly wage while working just as hard.

So, when does it make sense to abandon tipping in favor of raising restaurant prices so that all staff is paid fairly? Or would customers balk at that?

Sara Clifton is a mathematics professor at the University of Illinois who specializes in modeling complex social behaviors. In a recent paper, she created mathematical models of two competing restaurants, one with conventional tipping and one without. The paper was published in the Feb. 8, 2018 issue of Chaos, a journal from the American Institute of Physics.

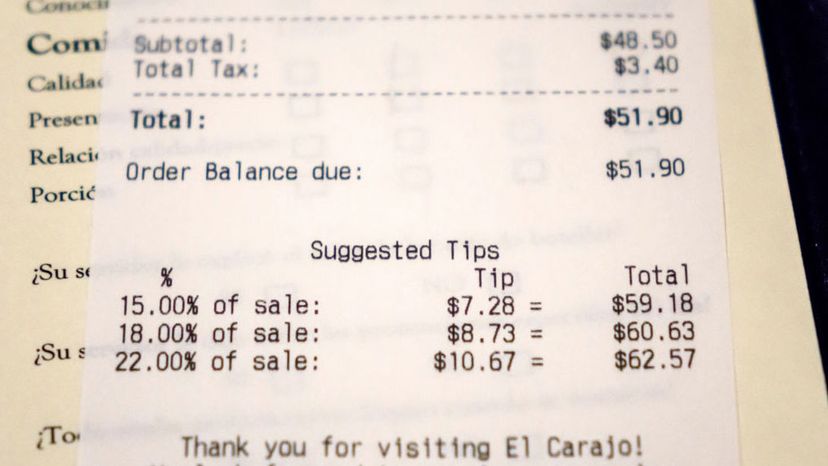

The key variable in Clifton's models is the average tipping rate. Tipping rates have been creeping up over the past few decades, from 10 percent to 15 percent and now close to 20 percent in major U.S. restaurant markets.

Clifton's models are designed to be as simple as possible, with every player in the system motivated purely by monetary gain. When cooks are paid better, they're more likely to stay, meaning that food quality goes up. When waiters are paid less, they're more likely to leave, affecting service quality. But eventually, the waiters would return if diners flooded the restaurant because of food quality which would presumably mean more profit and higher wages for all.

Advertisement