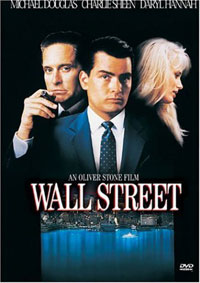

Photo courtesy Amazon

The film "Wall Street" epitomized the world of hostile takeovers in the 1980s.

|

There are several reasons why a company might want or need a hostile takeover. They may think the target company can generate more profit in the future than the selling price. If a company can make $100 million in profits each year, then buying the company for $200 million makes sense. That's why so many corporations have subsidiaries that don't have anything in common -- they were bought purely for financial reasons. Currently, strategic mergers and acquisitions are more common. In a strategic acquisition, the buyer acquires the target company because it wants access to its distribution channels, customer base, brand name, or technology.

These purchase factors are the same for friendly acquisitions as well as hostile ones. But sometimes the target doesn't want to be acquired. Perhaps they are a company that simply wants to stay independent. Members of management might want to avoid acquisition because they are often replaced in the aftermath of a buyout. They are simply protecting their jobs. The board of directors or the shareholders might feel that the deal would reduce the value of the company, or put it in danger of going out of business. In this case, a hostile takeover will be required to make the acquisition. In some cases, purchasers use a hostile takeover because they can do it quickly, and they can make the acquisition with better terms than if they had to negotiate a deal with the target's shareholders and board of directors. The two primary methods of conducting a hostile takeover are the tender offer and the proxy fight.

A tender offer is a public bid for a large chunk of the target's stock at a fixed price, usually higher than the current market value of the stock. The purchaser uses a premium price to encourage the shareholders to sell their shares. The offer has a time limit, and it may have other provisions that the target company must abide by if shareholders accept the offer. The bidding company must disclose their plans for the target company and file the proper documents with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The 1966 Williams Act put restrictions and provisions on tender offers.

Sometimes, a purchaser or group of purchasers will gradually buy up enough stock to gain a controlling interest (known as a creeping tender offer), without making a public tender offer. This bypasses the Williams Act, but is risky because the target company could discover the takeover and take steps to prevent it.

In a proxy fight, the buyer doesn't attempt to buy stock. Instead, they try to convince the shareholders to vote out current management or the current board of directors in favor of a team that will approve the takeover. The term "proxy" refers to the shareholders' ability to let someone else make their vote for them -- the buyer votes for the new board by proxy.

Often, a proxy fight originates within the company itself. A group of disgruntled shareholders or even managers might seek a change in ownership, so they try to convince other shareholders to band together. The proxy fight is popular because it bypasses many of the defenses that companies put into place to prevent takeovers. Most of those defenses are designed to prevent takeover by purchase of a controlling interest of stock, which the proxy fight sidesteps by changing the opinions of the people who already own it.

The most famous recent proxy fight was Hewlett-Packard's takeover of Compaq. The deal was valued at $25 billion, but Hewlett-Packard reportedly spent huge sums on advertising to sway shareholders [ref]. HP wasn't fighting Compaq -- they were fighting a group of investors that included founding members of the company who opposed the merge. About 51 percent of shareholders voted in favor of the merger. Despite attempts to halt the deal on legal grounds, it went as planned.

Next, we'll see how a company can defend against a hostile takeover.

| LBOs and Corporate RaidsLeveraged buyouts (LBOs) and corporate raids are variations on hostile takeovers. In an LBO, the buyer borrows heavily to pay for the acquisition, either from traditional bank loans, or through high-yield (junk) bonds. This can be risky, since incurring so much debt can seriously harm the value of the acquiring company. If the target company doesn't turn enough of a profit to balance the debt, the acquisition can be disastrous. Although it was popular in the late 1970s and 1980s, the current economic climate is not friendly to the LBO.

In a corporate raid, a company purchases another through a hostile takeover (often with an LBO) because their assets are worth more than the value of the company. As soon as the new owners complete the acquisition, they close the company and sell off all the assets. This often takes employees by surprise, since it can happen in a matter of hours. Like LBOs, corporate raids are out of vogue, mainly because stock prices are so high that it is rare to find a company that is undervalued relative to its assets. |