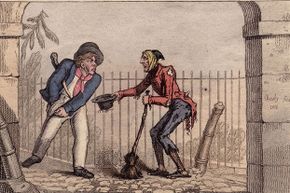

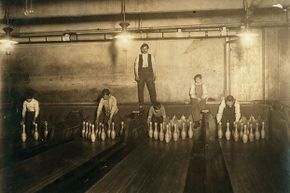

When Johannes Gutenberg introduced movable type to Europe in the 15th century, it revolutionized the world. No longer were scribes needed to create manuscripts by hand, one at a time. Mass copies of a document or book could be created with great speed. The early typesetters likely never dreamed their cutting-edge jobs would one day become obsolete, but those jobs vanished — just as innumerable other occupations have over the centuries, thanks to ever-changing technologies. Some morph into other careers. Others just disappear from history.

Based on projections from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the top occupations currently slated to become footnotes in our history books include word processors and typists, door-to-door sales workers and mail carriers [source: Forbes].

Advertisement

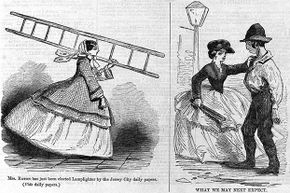

Are there any jobs that will never go away? It's hard to imagine a world without farmers, police officers and teachers, to name a few seemingly critical occupations. And, sure, if you go to a place that's dedicated to preserving the past, like a museum, a living history site or even a Renaissance festival, you'll find modern-day people doing very old jobs. In terms of widespread employment, though, who really knows what lies in the future? Perhaps our food will be grown by scientists, our streets patrolled by robots and our children taught by computers. Let's look at some jobs, once quite important — even critical — that have faded from view, in chronological order.