Thanks to books, movies and TV shows, many people have a clear mental image of the stereotypical private investigator. He works from a dimly-lit, cluttered, sometimes smoky office in a less-than-affluent part of town. There, he greets a series of walk-in clients -- often women -- who have been wronged in one way or another.

Usually, his job is either to find proof of wrongdoing or to make the situation right again. To do this, he gets useful information from witnesses and bystanders, sometimes with the help of false pretenses and fake identification. He tails witnesses, takes pictures, searches buildings and keeps an eye out for clues that others may have overlooked. Occasionally, his curiosity gets him into trouble, and he barely escapes being caught somewhere he isn't supposed to be. But eventually, he returns to his distressed client, letting her know that he's solved the case.

Advertisement

Lots of fictional detectives have contributed to this image, including Sherlock Holmes, Philip Marlowe and multiple film noir heroes from the 1940s and 50s. Today's pop-culture investigators, like Adrian Monk and Veronica Mars, are often a little quirkier than their older counterparts. They don't necessarily wear fedoras, work in questionable neighborhoods or even call themselves private investigators. However, they still appear as heroes who have a knack for digging up the right information at the right time.

But just how much of the P.I. lore is really true? How many of the events depicted in fiction are really possible -- or legal? In this article, we'll explore what it takes to become a private investigator and exactly what the job involves.

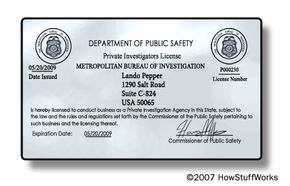

The first step to separating fact from fiction is to define precisely what a private investigator is. Essentially, private investigators are people who are paid to gather facts. Unlike police detectives or crime-scene investigators, they usually work for private citizens or businesses rather than for the government. Although they sometimes help solve crimes, they are not law-enforcement officials. Their job is to collect information, not to arrest or prosecute criminals.

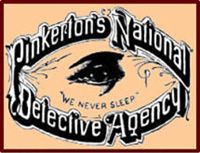

Private investigators have existed for more than 150 years. The first known private detective agency opened in France in 1833. In 1850, Allan Pinkerton formed Pinkerton National Detective Agency, which grew into one of the most famous detective agencies in the United States. The Pinkerton Agency became notorious for breaking strikes, but it also made several contributions to the fields of law enforcement and investigation. The agency takes credit for the concept of the mug shot, and the term "private eye" came from the original Pinkerton logo.

Today, about a quarter of the private investigators in the United States are self-employed. Of those who are not, about a quarter work for detective agencies and security services [source: U.S. bureau of Labor Statistics]. The rest work for financial institutions, credit collection services and other businesses. Many investigators choose to focus on a specific field of investigation based on their background and training. For example, someone with a degree in business might become a corporate investigator. An investigator with a background in patents and trademarks might focus on intellectual property theft. A certified public accountant (CPA) might specialize in financial investigation.

But regardless of specialization, a P.I.'s job is to conduct thorough investigations. We'll look at the investigative process in the next section.

Advertisement