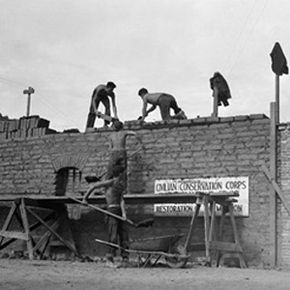

Things had never looked so bleak for the American people as in the early 1930s. By 1932, unemployment had skyrocketed to more than 20 percent, and the despairing country was ready for a change in leadership. To that end, the people elected Franklin D. Roosevelt, who immediately set to work implementing programs aimed at alleviating the hurting economy. And we do mean immediately -- he called Congress into an emergency session to push through such programs during his first 100 days in office. Though not all of these initiatives worked out as well as he had hoped, one stands out as especially successful and popular: the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC).

The CCC was a kind of pet project for FDR, who had already established his dedication to conservation projects when he was the governor of New York. As the CCC Legacy Web site explains, the program was a way of solving the problems of two "wasted resources": unemployed youths and the environment [source: CCC Legacy]. The idea was to put young men to work on special projects that pertained to land conservation.

Advertisement

Not only could needy families benefit from a son's steady paycheck, but the work itself could offer a facelift to communities while improving the local environment. What's more, the program was one solution to authorities' worries about the dangers of idle youths. Officials reasoned that if they kept young boys busy with work in the great outdoors, it would prevent these young men from slipping into an "underworld" life of crime [source: Barry]. It seems to have worked, as some officials credit the CCC with lowing the crime rate in communities [source: CCC Legacy].

Most consider the CCC a smashing success. In its nine years' existence, the CCC put nearly 3 million men to work. It also earned high approval ratings from the public on both sides of the political aisle. But, because such a program was unprecedented and needed to be put together so fast, it was no easy task.

Advertisement