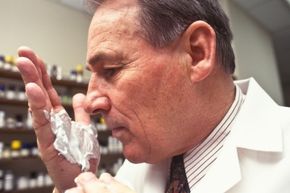

Right now, in a lab somewhere, someone is testing a scent combination for the 491st time. Months have been spent systematically adjusting ratios of woodsy to floral, looking for balance. Or rather smelling for balance: For perfumers, evaluation happens way back in the nose, via millions of olfactory receptors [source: Fox].

You may not know any perfumers by name, but you definitely know their work. Chanel's No. 5 (1921) was the brainchild of Ernest Beaux, perfumer to the Russian czar and pioneer of perfume synthetics [source: Chanel]. Jacques Guerlain created Shalimar (1925). Calvin Klein's Obsession (1985) was Jean Guichard. Sophia Grojsman made Eternity (1988). Dior's J'Adore (1999) was Calice Becker [source: Fragrantica].

Advertisement

Each of these perfumers blended essential oils, the aromatic building blocks of a perfume, and experimented with different ingredients and proportions until he found himself inhaling a scent that evoked something -- a feeling, a sense, a mood -- and "unfolded" perfectly from first whiff to final, fading waft.

This is the most visible aspect of the perfumery trade and certainly the most glamorous. But what perfumers actually create are simply scents, and those scents have endless applications. The "sensual jasmine" of a perfume. The "calm vanilla" of a body wash. The "clean and fresh" of a laundry detergent, "meditative lavender" of an aromatherapy candle or "fresh and soothing" white tea of a Westin hotel lobby [sources: Starwood, Palmer].

Scent formats are countless. Perfumers – "noses" in industry speak -- are not. Perfumery is an exclusive line of work, to put it mildly. It's also somewhat mysterious, a unique blend of art and science that seeks to define, in olfactory terms, the undefinable.

Advertisement