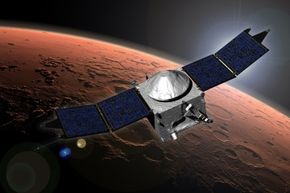

As a spacecraft called MAVEN hurdled toward Mars, NASA prepared for data that could reveal the planet's atmospheric history. After achieving orbit on Sept. 21, 2014, MAVEN and its team have begun examining how and when the Martian atmosphere degraded, as well as how and when the planet's liquid water disappeared. Eventually, we may know what exactly happened to the red planet -- how Mars became incapable of supporting life [source: NASA].

The MAVEN orbiter is just one of many missions in which astrobiologists play a critical part. NASA defines astrobiology as "the study of the origin, evolution, distribution, and future of life in the universe," and the field informs a lot of the agency's work [source: NASA]. Yet astrobiologists are a rare breed.

Advertisement

Astrobiology was really only recognized as its own scientific area in the last couple of decades [source: NASA]. Not that it's a new concept – NASA has been studying the possibility of extraterrestrial life since the 1960s, only it was "exobiology" back then [source: NASA]. The SETI Institute, which also searches for extraterrestrial intelligence, has been around since the mid-1980s [source: SETI]. But it was all considered at least a little bit fringe-y.

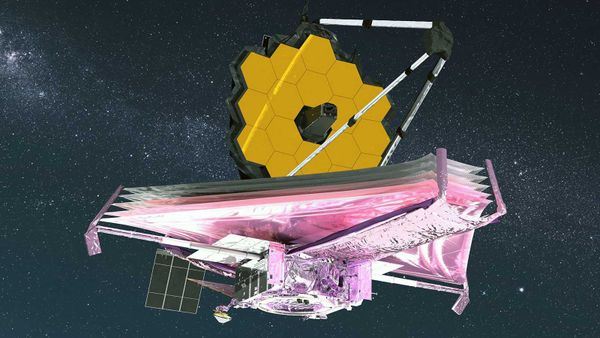

Now, astrobiology is a widely accepted discipline (there's even a primer!). NASA's Mars orbiters and rovers, satellite-based experiments placing microorganisms in space, and telescopic search for potentially habitable planets have brought astrobiology-related questions to the forefront of modern scientific inquiry [source: NASA].

Widely accepted doesn't mean widespread, though. Astrobiology is a tough field to break into. Universities typically don't offer bachelor's degrees in it. Even astrobiology doctorates are few and far between [sources: Dartnell, Lubick]. Research into extraterrestrial life is typically conducted not by "astrobiologists," but by teams made up of biologists, geologists, chemists, astronomers, physicists and others who contribute to a broad, in-depth understanding of life in our universe.

As NASA makes astrobiology an increasingly central focus of its work, interest in the field is growing. For budding scientists, the draw is obvious: Astrobiology applies the rigors of the scientific method to questions once considered the untenable purview of sci-fi fans.

Advertisement